- Lehman College >

- News >

- 2021 >

- Highlighting the Forgotten Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: 7 Questions With Professor Mark Christian

News

Search All News

Friday, February 20, 2026

CONTACT

Office Hours

Monday - Friday 9am - 5pmClosed Sat. and Sun.

RELATED STORIES

February 19, 2026

Highlighting the Forgotten Voices of the Civil Rights Movement: 7 Questions With Professor Mark Christian

February 11, 2021

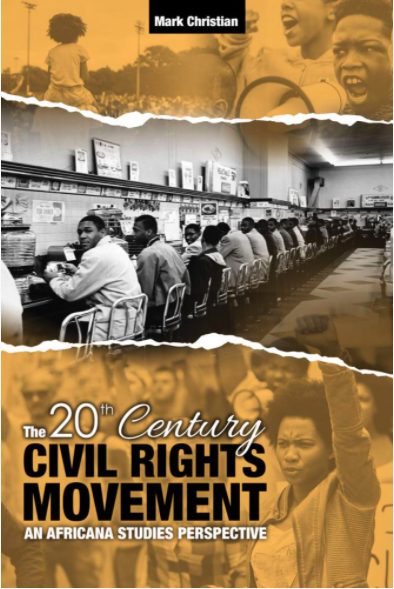

Mark Christian, an Africana Studies professor at Lehman College, has long been critical of how academia approaches the Civil Rights Movement: Too often, he said, scholars overlook the lesser-known voices of the struggle, focusing instead on its most celebrated names and narratives. He challenges that with a new exploration of this critical segment of American history, The 20thCentury Civil Rights Movement: An Africana Studies Perspective (Kendall Hunt, 2021). The book, his fifth, was published last month and takes pains to spotlight the organizers and writers whose voices have been ignored as well as those who knew Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X on a personal and professional level. We spoke with him about the work and what it adds to discussions about the era.

Q: In The 20thCentury Civil Rights Movement: An Africana Studies Perspective, you center men and women who were on the frontlines of the fight for racial justice and equality but whose stories and contributions are often omitted. Why do you think authors and historians have paid so little attention to them?

A: There are several reasons why the less well-known heroines and heroes of the Civil Rights Movement often don’t gain historical notice. Charismatic leaders tend to get the headlines due to their fame and ability to claim the spotlight, and ivory tower scholars also tend to look for the "big fish" and forget the grassroots. They see that as their path to receiving Pulitzer Prizes and other big awards from the established hierarchy in the academy. It is rather salient in terms of African American history—it's something I find despicable, but it is power and privilege at work.

Q: How does your book counter that?

A: The perspective I created fundamentally was to employ the biographies and memoirs of those closest to the movement: Harry Belafonte, Dorothy Cotton, Daisy Bates, John Lewis, Coretta Scott King, Bernard Lafayette, Sarah Keyes, Amelia Boynton Robinson, Jo Ann Gibson Robinson, Constance Baker Motley, and others. These individuals and more were leaders in the movement's era who often get lost. Maybe not so much John Lewis, but he's still not used enough as a resource by mainstream biographers.

I also made use of biographers from the African American community: L.D. Reddick, for example, wrote the first biography of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., published in 1959, and there is pioneering work by Lerone Bennett, Jr., who mainstream scholars largely overlook. He was a brilliant historian and biographer of Dr. King. In a sense, I'm stating to readers, ‘You need to consider these writers and activists when studying the Civil Rights Movement.’ I've challenged future scholars to go back and return, in a Sankofa sense, to the sources of African American historical and sociological scholarship. Lastly, I referred to Dr. King’s books often, as they are rarely cited—this may seem odd, but it’s a social fact. His books need to be known more widely and read more widely.

Q: Have you uncovered new truths or interpretations of that era?

A: I believe this book will shake up some scholarly dust in terms of rethinking the way the Civil Rights Movement is taught, referenced, and considered. For example, I devoted an entire chapter to Dr. King’s assassination because, again, the scholarship on it is largely ignored, and that is a disgrace to the truth and the democratic principles of this nation. The truth needs to be known in regard to who, why, and what killed Dr. King in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968. James Earl Ray did not kill Dr. King; the King family even acknowledges this point. Anyone reading my book will be moved to rethink their assumptions on the assassination—I'm confident of that.

Q: What was the book-writing process like?

A: The idea for this book has been with me for a long time, many years, and I was asked to consider writing it by a persistent acquisitions editor. Given the pandemic, I was able to concentrate beyond my normal schedule due to a lack of distraction, so the timing was optimal. I'm pleased with the end result. This book runs just under 370 pages. It’s a meaty book, one that I hope will endure the test of time.

Q: How long have you been writing?

A: Generally? I've been writing since my days back in Liverpool, where I grew up. I published some poetry as a teenager in the early 1980s. Then I began to do short articles for Liverpool’s Black community newspaper, The Charles Wootton News. Since I graduated from university with my PhD in 1997, I've published every year of my academic life. That includes books, scholarly articles, refereed journal articles, encyclopedia essays, book chapters, and a copious amount of book reviews.

Q: What texts are you currently reading?

A: I'm reading several books—that's the life of an academic. I came to Lehman in 2011 as a full and tenured professor—a level that takes great determination to reach—and I read books like a carpenter or a plumber uses their tools. I’m reading a book I've read before by Richard B. Moore titled The Name "Negro" and its Origins and Evil Use (Black Classic Books, 2013). It was first published in 1960. I like to read books from past generations in order to gauge what has changed and if they still have relevance today—most tend to.

Another book I'm currently reading is by Tommy J. Curry titled The Man-Not: Race, Class, Genre, and the Dilemmas of Black Manhood (Temple University Press, 2017). It is a powerful book about covert and overt attacks on Black men. Curry gives us some balance to the proliferation of feminist perspectives. For example, we are all familiar with the word "misogyny," but how many readers are familiar with "misandry"? I'm sure more readers are going to the dictionary for the latter word. That in itself should explain why Curry's book is so important to today's students.

Q: What advice would you give to students who aspire to write books themselves?

A: My advice to any writer is to be true to yourself and your passion. If you don't believe in what you're doing, the reader will soon figure it out. If you are bland, staid, and sterile in your writing, it will send folks to sleep. Be true to yourself always. I would hope any writer of a book has first published shorter pieces to get in the groove of publishing. A book is a big step, but again it's about sticking to your passion, what your voice is. And do not be afraid of criticism because it will come your way. When praised, smile. When criticized, smile. There will be those who condemn what you do, and others will praise what you do. Yet, the key thing is for you to believe in what you do. Do not get carried off your track by praise or criticism.