Lehman Prof Delson’s Nature Commentary Creates Buzz Around Early Human Migration to Europe

A new study published in Nature July 10, suggests Homo sapiens lived in Europe more than 200,000 years ago—150,000 years before what was previously thought—and paleoanthropologist Eric Delson, a professor in Lehman College’s Department of Anthropology, agrees.

In an accompanying commentary, published in the same issue, Delson wrote that the finding means our first modern human ancestors traveled afar earlier and more extensively from their origins in Africa than what most paleoanthropologists believe.

The new study, which Delson peer-reviewed for Nature, has garnered international attention, for its authors and for Delson, with interviews published in media outlets across the globe, including in Science, The Associated Press, Time and National Geographic.

“It is fantastic to know that we have significant evidence that our species, Homo sapiens, made it into Europe at such an early date,” said Delson from his research office at the Museum of Natural History in New York City. “In a way, the Levant region of the Middle East, including Israel, is an extension of Africa. But going further and crossing into southeastern Europe demonstrates that Homo sapiens was able to travel this long distance, expanding their range to follow game, perhaps, or searching for new areas to occupy.”

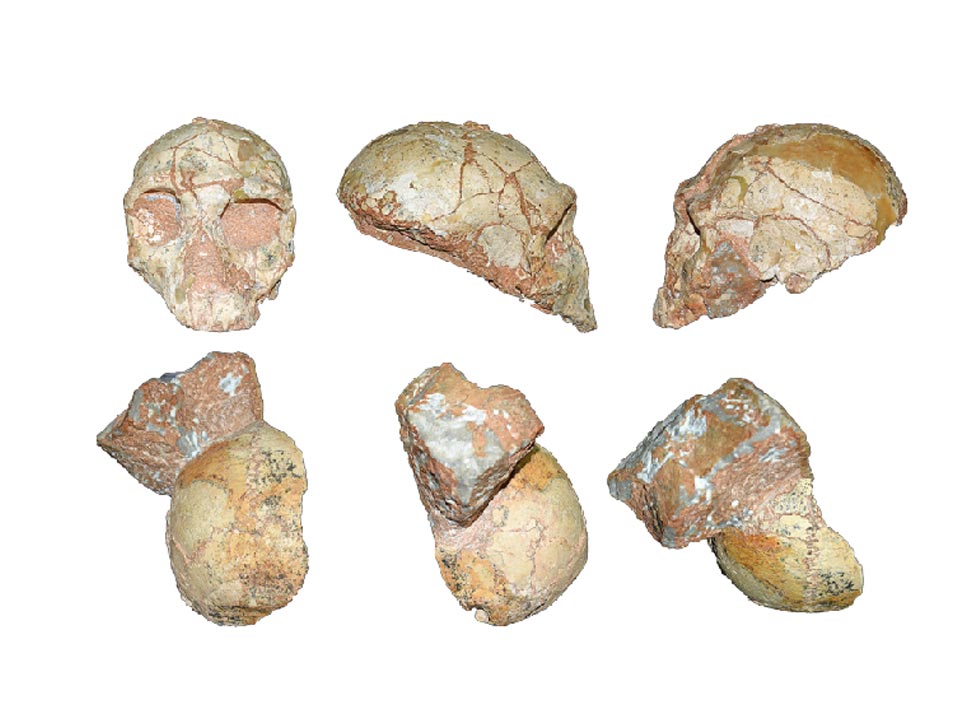

Based on two fossilized hominin partial skulls unearthed in the 1970s from a cave on Greece’s southern coast, the study came about when Katerina Harvati, a paleoanthropologist at Germany’s University of Tübingen, decided to test a theory about whether our early human ancestors had made their way out of the Middle East and into some of the warmer regions of Europe.

Harvati, who also has Lehman ties—she is a former Lehman adjunct lecturer--was granted permission to study the skull fragments, and using state-of-the-art computer imaging and 3-D virtual reconstruction, her team found that the fossils, long suspected to be from the same hominin, judged to be a Neanderthal, were different from each other, Delson said. The age of each fossil was determined using new uranium series dating techniques. The result: one fragment that was reconstructed to be from a Homo sapiens was from over 210,000 years ago, and the other, a Neanderthal fossil was from around 170,000 years ago.

This discovery put Homo sapiens in a region where it was previously thought to have arrived only a mere 50,000 years ago. (The earliest remains of Homo sapiens, found in Morocco, date back over 315,000 years.) It also meant that the two species of hominins possibly replaced each other across this area as they moved, Delson said, possibly to follow climate zones.

In his Nature commentary, Delson concludes that new genomic techniques will begin to bring even more discoveries about our early human ancestors to light, and help explain why—and how—they pushed north and westwards before dispersing around the world. Future studies may also focus on how Homo sapiens competed with the Neanderthals and ultimately succeeded them.