|

This Wednesday, April 22nd is Earth Day. It is the 50th anniversary of the first Earth Day in 1970. It may seem that this important day is eclipsed this year by the COVID-19 pandemic; unfortunately, we are at the very epicenter in the United States. However, this In Depth is equally about Earth Day and the pandemic, because there is so much that links the two.

If you have been following the pandemic closely since mid-February, as I have, you may have observed a striking similarity between it and the climate crisis: the way data have been used, the role of science, the array of public policy responses, the imposition of political narratives, the roles of municipal, state and federal governments, the role of the press, who the dominant players in the world are, and who the most vulnerable to the impacts are. The only distinctions I see between the two threatening processes are the time frame and the nature of the crisis itself. COVID-19 has been a crisis unfolding in a matter of months and the climate crisis is now well over a century in the making.

The similarities are not superficial, and are the result of the same underlying dynamics. I will briefly recount the history of the climate crisis, and I think you will see why I see that it has so much in common with the current pandemic. Some have even suggested there could be a link between the two.

A little background on climate change

The basic science behind the climate crisis, caused by human-produced greenhouse gases (GHGs), has been known for 120 years. The 'greenhouse effect' happens because atmospheric carbon dioxide, CO2, allows sunlight through to the earth, but reflects the infrared part of that light back to earth. It acts like a big infrared heat lamp, and the more CO2 and other GHGs there are in the atmosphere, the more intense is the lamp.

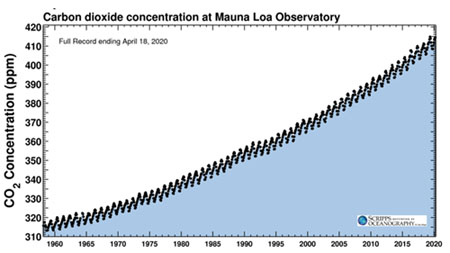

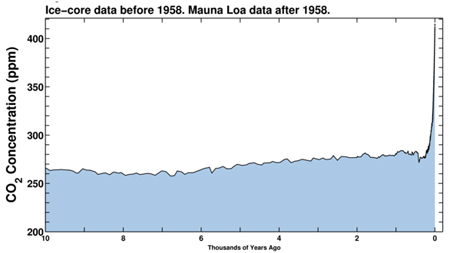

Ralph Keeling was the first to systematically measure atmospheric CO2, starting in 1958 when he found it was 316ppm, or Parts Per Million. For reference, on April 18, 2020, it was 417ppm, a 32 percent increase. You've probably seen the Keeling curve, but as a scientist I can't resist putting a few graphs in this piece, and this first one shows the change in atmospheric CO2 since 1958. In case you're wondering how big a change that is compared to a much longer period of time, take a look at the second graph which shows atmospheric CO2 for the past ten thousand years as determined by ice cores before 1958. Both graphs are from the prestigious Scripps Institute of Oceanography at UC San Diego. Ralph Keeling was the first to systematically measure atmospheric CO2, starting in 1958 when he found it was 316ppm, or Parts Per Million. For reference, on April 18, 2020, it was 417ppm, a 32 percent increase. You've probably seen the Keeling curve, but as a scientist I can't resist putting a few graphs in this piece, and this first one shows the change in atmospheric CO2 since 1958. In case you're wondering how big a change that is compared to a much longer period of time, take a look at the second graph which shows atmospheric CO2 for the past ten thousand years as determined by ice cores before 1958. Both graphs are from the prestigious Scripps Institute of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

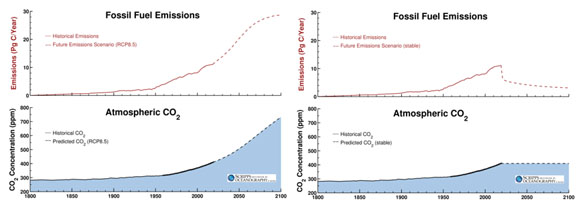

The final graphs compare fossil fuel emissions and atmospheric CO2 from the beginning of the industrial revolution and projecting changes through this century. The left graph shows a worst-case scenario where we basically fail to respond, and the right graph the best-case scenario in which we take drastic actions. Clearly, only the latter flattens the curve. The final graphs compare fossil fuel emissions and atmospheric CO2 from the beginning of the industrial revolution and projecting changes through this century. The left graph shows a worst-case scenario where we basically fail to respond, and the right graph the best-case scenario in which we take drastic actions. Clearly, only the latter flattens the curve.

Comparing the COVID-19 pandemic and the climate crisis

Early warning ignored

In 1988, NASA scientist, James Hansen, who did his work on 112th Street on the Upper West Side at the NASA Goddard Center, testified before Congress that the combustion of fossil fuels was a threat to the global climate. By the early 1990s, there was bipartisan support for taking action in response to the already alarming rise in atmospheric CO2, which Hansen posited was leading to rising global temperatures. But nothing much happened as the fossil fuel industry mobilized to protect its business.

The COVID-19 threat arrived much more quickly, but also not without warning. In fact, the warning first came after the SARS epidemic in February 2003. You may have seen a clip from 2005 in which then President George W. Bush laid out the critical urgency of developing national plans to respond to a pandemic just like COVID-19. Here, the comparison with the climate crisis is poignant because it was President George H. W. Bush who, in 1989, almost backed a strong response to rising atmospheric CO2 but then failed to act when John Sununu, his chief of staff intervened.

Science downplayed and scientists censured

The past two months have passed so quickly that it is almost difficult to remember that Fox News pundits initially labeled the threat of COVID-19 a hoax created by Democrats. That was long after reliable models from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and elsewhere predicted dire consequences in the U.S. if there was not a drastic and rapid response to the spreading infection. But the scientists and doctors inside the CDC and U.S. Government were afraid to be as blunt with the President as they needed to be. They self-censured, or when they did speak up they were ignored or chastised. Again, the parallel is striking. George W. Bush actively suppressed the testimony of James Hansen, and non-scientists in the White House redacted his written statements and screened his talks at climate conferences. President Trump has tried at times, though mostly unsuccessfully, to squelch the information given by Dr. Anthony Fauci. The current president's disregard for facts and data have had deadly consequences, as have those of George W. Bush.

Delayed responses and missed opportunities

Beginning in late 2019, the data about the outbreak in Wuhan, China, indicated that the new virus was highly transmissible and also deadly. International public health experts and the World Health Organization (WHO) began issuing warnings, and the U.S. government was briefed soon after about the potential of a pandemic. By now, we understand the cost of the delayed U.S. response in lives lost and in people's economic well-being.

Fast forwarding from the 1990s to April of 2020, we have now progressed beyond Hansen's predictions of how rising global temperatures could increase the speed of the melting of glaciers, increase the intensity of storms, and result in the loss of coral reefs and untold numbers of plant and animal species. We have witnessed all of these things happening in the past year. We have not flattened the curve when we could have. The consequences of this will, according to climate scientist David Archer, "last longer than Stonehenge…than nuclear waste…than the age of human civilization."

Roles of municipal, state and federal governments

The crossed purposes and actions of the federal and state governments have been marked this past week, with ongoing sparring between Gov. Cuomo, Mayor DeBlasio and President Trump. Most state governors have acted in the absence of, and often in contradiction, to the federal government. Federal inaction and incompetence have been offset by the actions of many of these governors. Here again, the comparison to the climate crisis is germane. States like California, New York and others have mapped out bold responses to climate change, vowing to stick to the Paris Agreement as the Trump administration abandons it. The Trump administration has sought legal action against California's clean air standards and tailpipe emission guidelines. The states have been critical in reducing the impact of the disastrous climate and environmental policies of the federal administration, but alone they are not able to compensate sufficiently for federal inaction and the systematic undoing of the environmental progress made by the Obama administration.

Who are the most vulnerable?

The Bronx is being disproportionately affected by COVID-19, with the highest rate of infection per 100,000 in the City, more than double that of Manhattan. The Lehman community has suffered tragic losses so far and the entire borough is hurting. It is well-established that long before this crisis, the health of Bronxites and their access to healthcare was among the worst in New York State.

Those factors that increase vulnerability to the coronavirus are in abundance: diabetes, heart disease, asthma and others. Those same residents were also far more likely to be essential workers, and/or lack the financial resources that would allow them to survive very long if unemployed. They have had the greatest unavoidable exposure to infection. It is no surprise that the Bronx has the highest rate of infection.

Crises greatly amplify inequity. In contrast, the better off residents of New York have been able to self-isolate, procure food safely, access digital resources, and in great numbers escape the city. This past Sunday, The New York Times launched an extended project titled, "The America We Need." In the first installment, David Leonhardt and Yaryna Serkez show in a series of graphs, " A Portrait of a Vulnerable Nation." The problem of inequity is painfully obvious.

The impact of the climate crisis follows the same pattern. Inhabitants of Pacific Island atolls, residents of Bangladesh, Alaskan indigenous peoples and many others are the first to be displaced by rising seas. But many others who live under the most precarious circumstances, including the Bronx, are also the most vulnerable to mega storms, heat waves and other consequences of climate change.

Witness the aftermath of Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. The climate crisis is an enormous disaster for social justice and equity; it will eventually threaten the lives of hundreds of millions of the most vulnerable people on earth. In addition to that, the pollution from burning fossil fuels kills four million people around the world every year. Those with means will move out of harm's way and will maintain their lifestyles virtually unaffected, only occasionally experiencing some of the consequences, while continuing to add to the problem.

Have we learned anything?

We can't answer this question yet for COVID-19. At least by now a majority of Americans are convinced that human activity is causing climate change. It has taken fifty years of accumulating data and communicating to the public. States, municipalities, organizations and millions of individuals have made adjustments to reduce their carbon footprint. We don't yet see a result of that effort on the Keeling Curve at the beginning of this piece because the major players, national governments like the US, China, India and many others, have not been willing to risk the political fallout of doing the right thing. They are the heavyweights and must act for significant improvement to happen. Just like President Trump resisted the reality of the COVID-19 pandemic out of fear that the economy would crash and ruin his chance of re-election, every national government has in one way or another failed the test of courage, and refused to acknowledge the data on the climate.

It is clear that one of the common causes in the U.S. of both crises is our virulent form of capitalism that has increasingly favored those who have over those who do not. Have we reached the point where this American original sin will be atoned for as it partially was during the time of the New Deal?

Our individual and corporate addiction to high-carbon-consuming lifestyles is a major cause of the climate crisis. One of the results of most of the country being isolated and at home during the coronavirus outbreak is that air pollution and GHG production has dropped dramatically—NO2 by as much as 40 percent in some areas of the world. Meetings we planned to attend have been cancelled or conducted online. We should now be asking ourselves whether we need to go back to having all those national meetings where people fly in from all corners of the country, contributing significantly to GHGs in the atmosphere. In academia, we like to think of ourselves as being enlightened and guided by science, so I find it puzzling that we academics haven't tried harder to reduce our carbon footprint by more creatively using the internet. Maybe one large meeting a year, hosted by multiple related societies could dramatically reduce air travel. Are we ready to think and act responsibly when we are the ones having to give up something?

What is Lehman doing about the climate crisis?

I am writing this in a desperate time, when it is natural to feel overwhelmed about both of these simultaneous crises. We have experienced both of them acutely in the last ten years: Hurricane Sandy, Hurricane Maria, and now COVID-19. We are probably past the tipping point for some of the consequences of burning fossil fuels, and we will have to live with the aftermath of COVID-19 for some time, enduring the human loss and the financial ruin it is causing.

There is no point in sugar-coating the realities we face. Yet, despair is not really an option we can choose. Nor is hope without a basis. I have always felt privileged to work in a CUNY college because, as daunting as the societal challenges around us may be, CUNY is a beacon of hope where I can see positive change every day. I am inspired by the dogged determination of students, staff, faculty and administrators to see our educational mission through, knowing how important it is in addressing the gapping inequalities that exist.

There is no point where a switch is thrown and all is lost. There are some tipping points for sure, but much of what we face is on a continuum. We may no longer be able to prevent the world's average temperature from rising more than 2oC, a threshold that many scientists see as critical, but we can still have a positive impact and prevent it from going much higher.

Lehman College has been at the forefront of CUNY for many years in taking steps to lower our carbon footprint. We've been recognized for that work by CUNY; when the CUNY Sustainability Award was established in 2008, Lehman was the first to win that award as one of the first schools in the CUNY system to address redirecting compostable garden and food waste through innovative solutions. The College has been composting garden waste since 1996 and food waste since 2009; about three years ago, we added food waste from the cafeteria. We produce about nine tons of food waste each year on campus, but now we give it away, an amazing 1.3 tons, as food-grade quality compost. It goes to community gardens in the Bronx. With the help of Senator Alessandra Biaggi, we received a State SAM grant of $340,000 to expand our composting capacity.

The College has pursued other sustainability actions as well through innovative efforts led by VP Rene Rotolo and Director of Environmental Health and Safety, Ilona Linins. In our forthcoming strategic plan, we need to make further major commitments to do all we can as a campus community to reduce GHG emissions.

I came across a statement that inspired me in the April 2020 Earth Day issue of that venerable scientific journal, Rolling Stone. It quoted writer Mary Annaïse Heglar, who recently tweeted, "I don't care how bad it gets…I don't care how many thresholds we pass. Giving up is immoral." She went on to say, "I think hope is really precious, and the most precious thing about it is that you have to earn it…you have to go out and make your own hope."

That is what I see around me at Lehman College. We are making our own hope, and in doing that individually, we are making each other hopeful. On this fiftieth anniversary of Earth Day, let's renew our commitment to the environment, and to each other, and in so doing, continue to make our own hope in concrete ways that will make a difference for the environment and for social justice.

Daniel Lemons

@LehmanPresident

Previous messages from President Lemons can be found here. |